| Issue 2, Spring 2003 | ||||

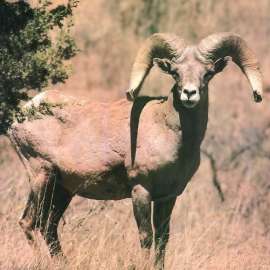

In Depth: Bighorns on the Brink

Catch them perched precariously on a ledge overlooking your hiking trail, and you can consider yourself lucky. Desert bighorn sheep are one of the most majestic mammals native to the desert Southwest. Several national monuments in Arizona offer safe harbor for these highly sensitive and mobile species. Although desert bighorns are doing moderately well in the Southwest as a whole, the populations that traditionally roamed the Tucson Basin have become isolated and unstable. Today, for example, less than 100 desert bighorn sheep occupy Ironwood Forest National Monument. Human impacts have rendered this herd the last bighorn sheep population in Pima County, where they live virtually isolated in a sea of human development. This, in itself, is an impediment to long-term viability of this herd, as there are no nearby populations with which to exchange genetic material or to re-colonize habitat in the event of a die off from disease or other factors.

Many game managers believe the lack of available watering sources is the primary reason for bighorn decline. The AZ Game and Fish Department (AGFD) has constructed artificial watering holes in remote mountain rangers to combat the deficiency in more than 100 locations around the state. While many natural sheep watering sources have gone dry or been destroyed, desert bighorn sheep have evolved over thousands of years to survive on very little water. There is little conclusive evidence that these watering holes help maintain sheep viability. "Mule deer, feral burros, and domestic livestock are drawn to these waters," says Jason Williams, AWC Central Mountains/Sonoran Desert Regional Coordinator. "These animals compete for forage with sheep and in some cases facilitate the spreading of disease and parasites to bighorn herds. It's clear we need more studies to determine if these artificial waters are helping or harming desert bighorn survival." Since 1933, desert bighorn sheep have been classified as a wilderness species, meaning they do tolerate human contact and development easily. Their viability depends largely on successful reproduction and herd intermixing. In Arizona’s popular outdoor destinations, such as Ironwood Forest, this isn’t an easy task. Popular hiking trails keep human traffic bustling in the monument eight months out of the year, while new roads and existing highways sever traditional sheep migration routes to neighboring populations and forage grounds. “Increased amounts of recreation in the monument will likely have a negative influence on the population,” says Dr. Paul Krausman, professor and research scientist in wildlife and fisheries management at the University of Arizona in Tucson. “It becomes important to document if and how recreation is increasing and if it affects the bighorn in Ironwood.” Several populations in Arizona are known to have stopped breeding altogether, from seemingly non-intrusive hiking near traditional habitat areas, particularly near Push Ridge and Ragged Top mountains. If hikers are present at higher elevations, sheep can’t escape to the cliffs above their forage grounds when frightened by hikers at lower elevations. Moreover, roads can crisscross sheep habitat and bisect traditional migration corridors between breeding populations, preventing genetic mixing that is essential for herd health. The late biologist Michael Seidman, who passed away in January, advocated that hikers avoid sensitive sheep areas like Ragged Top during the spring lambing season. Seidman balanced his support of restricted hiking with the fact that numerous other trails offer the same challenging terrain without disturbing these majestic animals. The AGFD will be examining how humans are influencing the herd through recreational activities and mining. Studies will be conducted by AGFD biologists and graduate students from the School of Renewable Natural Resources at the University of Arizona. Wildlife managers at Ironwood report that they do annual bighorn sheep counts and monitor sheep movement between the Sawtooth and Silverbell ranges. Sheep remain legally hunted in Arizona, and the Arizona Department of Game and Fish lists desert bighorn sheep on their website as part of their “Big Game Species” directory. Given the relatively small size of Ironwood Forest National Monument and the lack of nearby populations and accessible habitat, it is essential that Ironwood Forest National Monument be managed to more effectively prevent bighorn habitat fragmentation and herd disturbance.

The AWC wilderness proposals for Ironwood Forest National Monument begin to rpotect the best of core habitat and several travel corridor areas for sheep using the West Silverbell and Sawtooth mountain ranges. A more formidable challenge will be protecting the state lands in between these core habitats, especially given the propensity of state lands to be developed for the highest economic value. "Bighorn sheep represent a flagship species for wilderness of the desert Southwest," says AWC's Williams. "Without these animals, we will lose the very essence of Arizona's wild heart and the purpose of public lands." You can get involved in protecting bighorn sheep through wilderness advocacy with the AWC! Stay tuned for future planning efforts in Ironwood Forest National Monument, beginning this summer with public meetings hosted by the Bureau of Land Management. References for this story are available upon request.

|

||||

Make your spring and early summer outdoor plans here! Visit our comprehensive

list of day outings, inventory trips, meetings, and upcoming AWC events for

the latest in wilderness “happenings” around the state.

Make your spring and early summer outdoor plans here! Visit our comprehensive

list of day outings, inventory trips, meetings, and upcoming AWC events for

the latest in wilderness “happenings” around the state.